Sabbath Day – Everyday Astonishment

For six weeks now I have let my Sabbath Day function as the center around which I have organized a week of reading different national literatures.

- FRANCE: Jean Paul Sartre (who refused the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1963).

- FRANCE: André Gide (Nobel Prize in 1947); Albert Camus (Nobel Prize in 1957); as well as Victor Hugo and Simone de Beauvoir.

- RUSSIA: including Tolstoy, Chekhov, and Turgenev.

- IRELAND: Seamus Heaney (Nobel Prize in 1995); William Butler Yeats (Nobel Prize in 1923); George Bernard Shaw (Nobel Prize in 1925); Samuel Beckett (Nobel Prize in 1969); and others.

- ANCIENT IRELAND: The Taín, Celtic Spirituality, St. Brenden.

- LATE ROMAN REPUBLIC: Julius Caesar’s Commentaries on the Gallic War

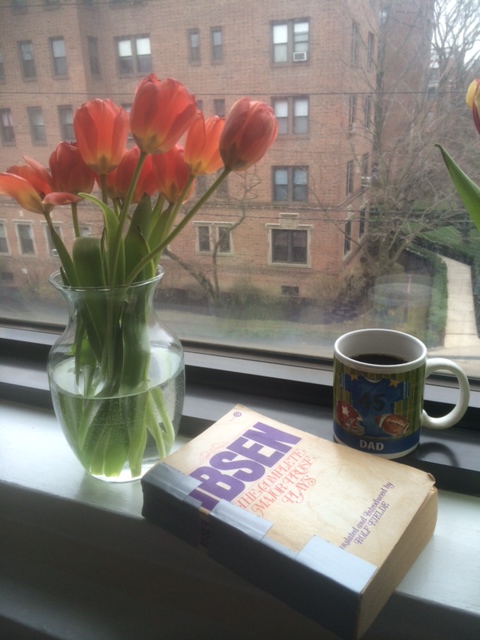

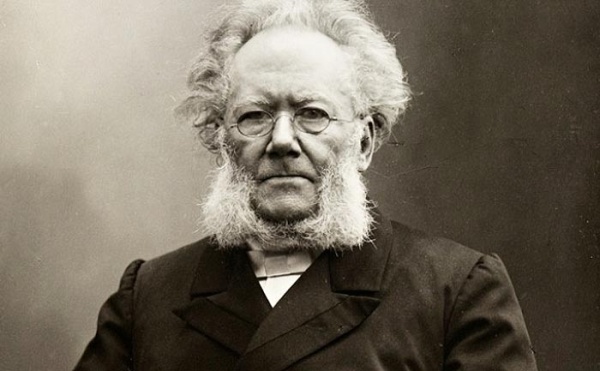

This past week I was drawn to SCANDINAVIA by a volume of the Complete Major Prose Plays by the Norwegian Henrik Ibsen, which I found on my shelf (translated and introduced by Rolf Fjelde). By the time I finished with it this week, the book was held together by duct tape and immensely more precious to me – filled with new notes, highlights, and underlines. I had read and enjoyed a handful of these before: Arthur Miller’s adaptation of Ibsen’s An Enemy of the People is one of my favorite plays of all time. Yet the back cover of this tattered paperback quotes the author himself as saying

Only by grasping and comprehending my entire production as a continuous and coherent whole will the reader be able to receive the precise impression I sought to convey in the individual parts … I therefore appeal to the reader that he [sic] not put any play aside, and not skip anything, but that he absorb the plays … in the order in which I wrote them.”

So I set out to read them all, in order. Though the last seven days encompassed the culmination of Holy Week and Easter, I carried this volume with me everywhere. I read in morning before the sun came up, late at night after everyone was asleep; it was the first book I have read on our apartment balcony and the first to greet the return of warm weather and sidewalk cafés. I was so surrounded by Ibsen’s prose that I dreamt in dialogue, seeing the characters blend in and out of one another’s dramas, conjuring alternative or extended endings for each story. And I managed all twelve of the prose plays, in order, with out skipping any:

- The Pillars of Society (1877)

- A Dolls House (1879)

- Ghosts (1881)

- An Enemy of the People (1882)

- The Wild Duck (1884)

- Rosmersholm (1886)

- The Lady from the Sea (1888)

- Hedda Gabler (1890)

- The Master Builder (1892)

- Little Eyolf (1894)

- John Gabriel Borkman (1896)

- When the Dead Awaken (1899)

My head is swimming with Ibsen’s social criticism, psychological exploration, individual struggle, and the pain of so many characters; the yearning for freedom, happiness, unbounded “life, life, life” – as well as the reality of limits, the presence of death, the working out of grief and guilt, and the complexity of relationships (especially marriages). Ibsen is widely considered the best playwright since Shakespeare, and he was nominated three times for the Nobel Prize in Literature. It is a mark against the Nobel Prize, which has disproportionately been given to a Scandinavian, that Ibsen never received one!

As a bonus, I found that many of the plays are available on youtube, as performed for a BBC television series Play of the Month. Anthony Hopkins and Diana Rigg made me weep with their portrayal of grief in Little Eyolf. Wallace Shawn wrote a screen play for The Master Builder, released on film last year (2014), which absolutely tore me apart emotionally. Lisa Joyce‘s portray of Hilda terrified me.

* * * * *

As I settled on Scandanavia, I pulled from my shelf a volume of collected poems by the Swedish poet Tomas Tranströmer, who deservedly won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2011 for his “condensed, translucent images that give us fresh access to reality.” He writes with “a sense of mystery and wonder underlying the routine of everyday life, a quality which often gives his poems a religious dimension.” The title of this post, everyday astonishment, is his.

Serendipity of choice for my reading each week continues to operate. As it turns out, Tranströmer died two weeks ago, on March 26th, at the age of 83. In the lead-up to Holy Week I missed the obituary. Here is his poem, After a Death:

Once there was a shock

that left behind a long, shimmering comet tail.

It keeps us inside. It makes the TV pictures snowy.

It settles in cold drops on the telephone wires.

One can still go slowly on skis in the winter sun

through brush where a few leaves hang on.

They resemble pages torn from old telephone directories.

Names swallowed by the cold.

It is still beautiful to hear the heart beat

but often the shadow seems more real than the body.

The samurai looks insignificant

beside his armor of black dragon scales.

* * * * *

And finally, I quietly perused my paperback copy of Dag Hammarskjold’s posthumously published Markings. I received this book the year I was confirmed and it inspired my new-forming faith:

“In our age, the road to holiness necessarily passes through the world of action.”

Hammarskjold, a Swedish diplomat and economist, served as the Second Secretary-General of the United Nations (a position he held from 1953-1961) and was the only one to die in office. (He was also an avid hiker and lover of nature). Hammarskjold was killed in a plane crash on his way cease-fire negotiations in Congo in 1961 (quite possibly shot down by mining interests who profited from the conflict). He received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1961, having been nominated before his death.

Markings documents the inner spiritual life of a public man of action, drawing heavily on mystics like Meister Eckhart and Jan van Ruysbroeck. The markings were entries in a diary Hammarskjold began keeping when in this twenties and continued to fill until his death. They were his compass in difficult times. The introduction to my paperback copy, written by W.H. Auden, cites a radio interview Hammarskjold once gave in which he said:

But the explanation of how man should live a life of active social service in full harmony with himself as a member of the community of spirit, I found in the writings of those great medieval mystics for whom ‘self-surrender’ had been the way to self-realization, and who in ‘singleness of mind’ and ‘inwardness’ had found strength to say yes to every demand which the needs of their neighbors made them face, and to say yes also to every fate life had in store for them when they followed the call of duty as they understood it.

This has been a very rich reading week.

May your sabbath be as rich when you find it.

Trackbacks